Please stop fetishizing the campus...

This grew out of a response on Facebook to an IHE column by Josh Kim recently posted, titled 10 Inconsistent Ways That I Am Thinking About the Future of Academic Work. I was content with leaving this response as a social media reaction, but I was prompted and prodded a bit to clean it up a bit and write about it. It seems like I ended up writing more than I intended. Anyway, I am not interested in submitting it to IHE as an op-ed, so I figured I'd post it on my own blog (for whatever it's worth - maybe I can get the google juice instead of IHE 🤣). Josh posts 10 things that give him cognitive dissonance about remote work in higher education, but I find the list rather contrived. Worse, I find it to be a list that might live on someone's blog as a quick pondering rather than on something that purports to be a higher-ed news outlet.

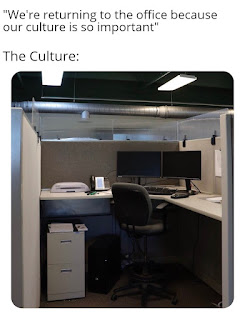

tl;dr: For what it's worth, I think the fetishization of campus culture, exhibited both in this article and elsewhere in the world of academia, is what's preventing us from truly integrating new, smart, and healthy procedures that bring different together people, from many different locations, to accomplish goals. I don't think that this article needed to be written. Even as a "devil's advocate" it does absolutely nothing to advance real discourse in modern work and learning by fetishizing a past that may have never existed, or existed only for those with privilege. This is harmful not just to employees but to prospective students who want that "real campus experience" - which again, may have never really existed, except maybe for some very privileged folks.

Suggested reading voice for what follows: Lewis Black (just sayin') 😆

~~~~~

Here are some direct responses for each of the 10 items. I've included the original so as to minimize unnecessary tab-flipping. Any bolded or italicized text in the original is my own for emphasis.

#1 - "I want everyone to be around on campus for casual chats and unscheduled run-ins, yet I’m flexibly working from home sometimes with no set schedule."

Response: There's really a lot of unpack here, and it all really begins with privilege. You have to be privileged to not have a set schedule. As a staff member, I've worked remotely (at least for some parts of the year) since 2013, and I always had a set schedule. Even before the pandemic, my campus basically tells teleworking and flex-schedule staff that they need to be available between 10am and 3pm when teleworking and using flex time so that other employees could reasonably schedule meetings with them. Having no set schedule just speaks to your privilege as a faculty or faculty-like position. This kind of telework/flexwork is something that campuses are already familiar with. Faculty have been doing this for as long as I've been in Higher Ed (20+ years). It's really not rocket science. That flexibility has now been given to other staff members of the university, but people are freaking out because they are losing the privilege of being the only ones to telework unquestionably, and possibly having to plan to meet with people (*gasp*😲). Prior to the pandemic, I was building a case to make an argument for my own telework. I had a spreadsheet of metrics and work produced both for F2F work and during the periods I was remote (usually summers) that basically showed that I was as productive at home with fewer interruptions. Furthermore I saved 43 days a year in commuting (over 1000 hours in a year, and over $3000 in commuting costs). As I was chatting with tenured faculty friends, I drew parallels between professional work and faculty. The response I got was "yeah, but faculty work even when we're not at our campus offices". I mean...huh?🙄😕. Let's normalize the fact that the staff are autonomous beings that can and do work productively when they are not in the office. This "I only think of you working when you are physically present in the office" from people who are highly productive away from the office really floored me🤯.

Being able to stroll onto campus whenever you want and expect to find folks available to just chat and have unscheduled run-ins is a privilege. Even if you work a "regular 9-5" those watercooler chats are a privilege. Some positions are just factory-like in the way some supervisors schedule work, which means that even your bathroom breaks need to be planned. For those folks interrupting them because you walked by their office means that you're an inconsiderate human. Furthermore, asynchronous remote/digital communities have been a thing since the early days of BBS and IRC. Cultivating a community is hard work, and everyone must work at it, otherwise, it won't be a thing. There's no "if you build it they will come." You can have the illusion that watercooler talk "just happens," hence cultivating a community seems seamless in a F2F context, but you're really not examining the factors that lead you there, and who's privileged.

~~ ~~

#2 - "When colleagues are on campus, I want to be able to come to their offices for unscheduled conversations. At the same time, much of my on-campus time is spent with my door closed and on Zoom meetings."

Response: Excuse me now? 😮 First of all, this is really an expansion on point #1 for those unexpected run-ins, but...what gives you the right to come to people's offices for unscheduled meetings? Now, to be fair, when I run errands on campus and I walk by the offices of colleagues whose doors are open (and I am acquainted with), I will pop my head in to say a quick hi or waive a hand, but I won't just expect that they'll be ready for my every whim and need for conversation. I'm not sorry to say, that I don't want someone coming into my office for unscheduled conversations. I've seen, first hand, the damage these things can do. Half of a day's productivity can be sucked away from these people-pleasers (anecdotally speaking) and really conscientious people stay late at work (without extra pay) to get stuff done that they should have done during their workday if it weren't for interruptions. If I am working on something that requires my attention these unexpected interruptions are disruptive. This mindset privileges the disruptor. At the same time, you close your doors to attend zoom meetings...sooo... if you don't want to be interrupted, what makes you think others want to be interrupted by you?🤔

~~ ~~

#3 - "At the end of each day, I find myself exhausted from Zoom meetings and missing the energy you get from being with smart people in a room. And yet, most of the meetings that I schedule are on Zoom."

Response: Most meetings are on zoom because it brings people in that are not physically proximal. It's an equalizer...and I can also mute the microphone of the dude who monopolizes the airtime 😉. You cannot do that in a F2F meeting. Additionally, when we have virtual meetings, everyone is able to share their screens, it's not privileged just for the host of the meeting, we can collaborate on documents, and be more productive, in my view anyway, having attempted to bring together faculty who were both on-campus and NTTs who were across the US and Europe. Even last year, when we met on-campus, I connected an OWL camera to the conferencing computer in the room, set it at the center of the conference table, and connected that to a digital projector to bridge the in-person crew with virtual participants. Even though my office is three doors down from our conference room, I also participate virtually. Why? I don't want to be in a room and masked for 2 hours, and I don't have a laptop to bring into the meeting to get work done during it, unlike all of our faculty. Being in my office allows me to facilitate a meeting while not wasting 2 hours of my productivity. Also, your issue isn't feeling exhausted due to "not being with smart people in a room". Those same smart people are on Zoom. Your issue is the overabundance of meetings and zoom fatigue. During this pandemic, we've had a proliferation of unnecessary, and long, meetings. At the end of the day, could your meeting have been a simple bleeping email? I am sure that if you had to go from meeting to meeting to meeting on campus you'd feel similarly exhausted. Be smarter with your meetings is my advice.

~~ ~~

#4 - "I firmly believe that talent is widely geographically distributed and that we can get the best people to work at our institutions if we are pro remote work. At the same time, I’m not sure what a critical mass of remote colleagues does to the culture of our residential campuses, and I worry about fully integrating and retaining remote academic staff."

Response: I am happy that you are concerned with integrating teleworkers into the overall organizational culture. It means that you're thinking and I think this is a good first step. However, the "residential culture" is at odds with telework. This is something that every manager needs to acknowledge and deal with. There is no question about it. What is it about "residential culture" that you value? And why do you want to preserve it? Who benefits from it, and who is excluded? Instead of thinking of residential culture think of a new space that is inclusive of everyone. And, if your response is "but think of the students!!!!" (I resisted my urge to put that in camel-case, I hope you appreciate the effort 😛), who do students really interact with? What sorts of norms are we unconsciously promoting? Let that percolate for a little while.

~~ ~~

#5 - "If my life circumstances were to change and I needed to move away from daily commuting distance to my campus, I think I could continue contributing productively as a remote employee. At the same time that I want flexibility for myself, I continue to wonder about the costs to institutional culture and innovation of the growing proportion of crucial academic staff members who now primarily work remotely."

Response: I direct you back to points 1 through 4. What institutional culture? What exactly are you trying to (unconsciously and uncritically) perpetuate? In my 20+ years in academia I've worked for some great departments (I count my current one as one of the better ones), and some really shit departments. As a union rep, and as an employee comparing notes with colleagues across campuses and other universities, I've also seen and heard of some real dumpster fires. Corporate Multinationals have been "remote" for decades and have been quite innovative. Why can't academia be the same? I find it hard to believe that people in academia, and people at Dartmouth no less, can't think outside their current box.

~~ ~~

Response: Welcome to the year 2000. We've just survived the Y2K apocalypse, which never came btw, and we've had successful internet-based distance education. You know what the problem is? Square pegs in round holes. You need to throw out paradigms that aren't working, that's a start to having your eyes open (like our good friend Darmok). If you fetishize campus, you'll continue to be confused. We need to move away from "is campus better than online?" - which has been definitely answered in the last 20+ years. I mean, look at all of the piss poor "research" that came out of the xMOOC fads of 2012-2020 and the ERT "research" that came out in the past couple of years. Few people were looking back at actual distance education research and everyone was discovering something and now (now! now!😲) people are convinced that we can create high-quality learning via distance education. It doesn't require a leap of faith, look at the literature and practices. The little cynic in me is thinking that learners are seeking alternatives to the "residential experience" that is more congruent with their lived lives, and since campuses that have traditionally shunned distance education now have no option but to confront is as an option. Ultimately, what really grinds my gears is that someone with Josh Kim's credentials should not be publishing this bullshit (🐂💩). Maybe 14 years ago when I first saw his posts on IHE he could get away with this 💩 but come on! We need some maturity in our field, now more than ever.

~~ ~~

#7 - "The future of residential education seems to be very much hybrid, as norms are evolving toward enabling students to retain instructional resilience even when traveling for sports or if they get sick. And yet, I find the HyFlex model of academic staff meetings (xMeetings) in which some people are together and some on Zoom to be almost always unproductive."

Response: Yes, the future is Hybrid. Our colleagues at the University of Central Florida (shout out to Kelvin and Tom) have been saying as much for the greater part of the last decade. Again, this is something that academics in similar positions to Josh should have known. I am a bleeping professional staff member, a cog in the machine, yet I've known this for a while. I say professional staff member to differentiate from faculty and faculty-like positions, which seem to be higher status than us cogs😑. Anyway, Why have I known this? Because I've cared to look beyond my immediate bubble and cast a critical eye on what's happening in higher ed (or at least some aspects of it, it's hard to keep track of everything).

I'd also be curious to know if there are campus meetings that Josh does find productive. As I mentioned above, personally, at times, I find them as black holes for my productive time. That said, in a zoom meeting I can find documents, share my screen without hassle, and have conversations without the need to move closer to the HDMI cable, plug in, configure resolutions, and then project what I want to show. I can also have conversations in the chat/backchannel without interrupting what's happening in the main verbal mode of communication. I can also share a document where we can swarm with my colleagues and do stuff productively. In F2F meetings, we talk for 2 hours and at the end, I feel dazed 😉.

But, let's turn our attention to HyFlex for a moment. HyFlex, both in the classroom and in a professional meeting setting hinges upon capability, capacity, and critical mass (3Cs if you will). If you don't have critical mass for the F2F modality, HyFlex just doesn't work in my opinion (as someone who has tried it both in teaching and in meetings). To make HyFlex work you need a good system where people RSVP for their chosen modality, and people can pick their preference based on their life situations (so no browbeating about coming to campus if you're local). If people can honestly state their meeting preferences we can determine if Hyflex is really an option or if it should be fully online - again, this has to do with critical mass! In AY21-22 there have been several meetings where someone caught something and they changed their RSVP last minute, or something came up and they couldn't make it in person, or had other meetings to make it to off-campus, or whatever. In years past they would have been absent, yet today yhey benefitted from the virtual meeting. yay! You know what's not so yay? The fact that I have a 2 hour commute to get to work (and another 2 hours back) to setup for a HyFlex meeting that ultimately moves online 1 hour before it's set to begin! Remember what I said about privilege? Percolate on that for a while.

Ultimately here, your problem with HyFlex meetings isn't HyFlex. Those can bring people together. What you probably don't have, and why your meetings suck, is an honest dialogue with your collaborators about meetings, good meeting procedures, and good meeting practices. It's like saying "I suck at speaking Greek" but you've never tried to learn Greek. What's your ultimate goal? To complain about how bad HyFlex meetings are? Or to actually make them productive?

~~ ~~

#8 - "The new reality of work everywhere is hybrid, and higher education must compete for talent across industries. The best people will go elsewhere if we don’t offer employment flexibility. How might we square this new workplace reality with the feeling that part of what makes academic work so fulfilling is the density of face-to-face interactions?"

Response: OK boomer...Josh, I know you're not a boomer, but that's certainly one boomer take on the situation. Again...welcome to...the 1980s? Because that's when we first start to see things emerge for Computer Supported Cooperative Work. I would go a step further and say that Hybrid isn't the reality of work everywhere. Remote is probably the "new normal" that many employees want (anecdotally from what I see on various social media platforms), but Hybrid is really the pull of the old guard trying to hold onto p-Work (my workplace equivalent to Dron's p-Learning) tooth and nail, so Hybrid is the uncomfortable compromise that just doesn't work for everyone. You know what would make a difference? Actually looking at the work and interactions we have with our colleagues and institutions and seeing what smart and healthy changes we can bring to the work so that the place isn't the primary means of identifying work. Ultimately, what works for you isn't necessarily what works for others. I'll go back to #1 and doing the hard work of cultivating communities. Lastly here, I challenge you to think deeper about that last point - fulfilling academic work. I've had my most fulfilling academic work be at a distance with colleagues from Scotland, Canada, Turkey, Egypt, Gyana, Greece, and many other places. I've only seen one of these folks IRL, but we certainly "see" each other virtually all the time. I guess I'll ask a question I typically ask graduate students: What is exciting about academic work? Why do you do it? If it's because it's a social club, then think deeper, and more critically, about what you do. I think the social aspect is important, and I care for the folks I collaborate with, but academic work always (for me) starts with some personal curiosity, and it's more fun to explore what makes things tick with others. I learn a lot from them (and I hope they learn something from me), but I don't need to be F2F for them (and I certainly don't need to commute 3-4 hours per day for it). I always wonder about the campus fetishists: how close do you live to campus, and is your parking free?

~~ ~~

#9 - "We have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to rethink almost everything about the university as a place of work. We are finally free to figure out what will work best for the people that constitute our institutions of higher learning. We can create new ways of working based on what we know about productivity and inclusion, and community, all facilitated by ubiquitous communication and collaboration platforms. But despite this opportunity, a large part of me longs for things to return to the campus-centric before days."

Response: Dude! Stop. Freakin'. Fetishizing! Just stop it! Bad academic! Look at your privilege. What are you longing to go back to exactly? Looking at it from the perspective of a graduate student, at my university, here's what campus-centric means:

- You need to come to campus to physically sign things

- You need to fax things in

- You need to meet in person with your advisor

- You need to deal with Boston traffic (which thanks to the MBTA these days will get worse!), and possibly pay tolls.

- You need to pay $15/day to park on campus

- You need to leave work early to come to campus to meet with someone who could have just zoomed you

- You need to take classes until 10:00pm to complete your master's degree. You arrive at 6pm (if you're lucky) after work, you need to scarf down something from the cafeteria quickly, and when you leave campus, you go home, sleep, and get prepped for another 15-hour day away from home/family/whatever.

Furthermore, from a staff perspective, those who make higher salaries can telework and had flex schedules prior to the pandemic, while those who were not paid as high (clerical work for instance) needed to come into campus, pay the $15/day, pay for gas, tolls, and take a hit on sacrificing personal time to commute so that someone can just come in when they like for those watercooler talks. Even if you took public transportation, like I did, that has its own challenges. And, Yes, /s tag here...🙄. So, tell me again, what are you longing for - just asking for a friend...

~~ ~~

#10 - "I’m convinced that the opportunity for flexible, hybrid and even remote work is optimal for individuals (including myself) who work in higher education. At the same time, I’m becoming less persuaded that flexible, hybrid and remote work is good for our colleges and universities."

Response: Would you please share with our class your rationale for your "it's not good! I feel it in my bones!" conclusion? What sorts of evidence do you have? Let me remind you that you need to point to evidence that is not confounded by COVID, Smallpox, general fatigue, poor pedagogy, under-prepared or un-prepared faculty members, and generally operating under uncertainty and doubt for the past couple of years. How exactly is "good" defined? And, good for whom? And, if in-person working (read: inflexible, on premises) work is not optimal for workers, what does that mean, ethically speaking, for forcing people. Even if anti-flexibility is good for colleges and universities, is it ethical to pursue that knowing that it's not good for the worker?

In the end, Anti-flexibility is a weird hill to die on.

Comments